Should we just live in the moment? In “Matter and Memory” the French philosopher Henri Bergson claims that this is not even possible.

1. Perception is physical

First of all: How do we perceive the “current moment” anyway? Bergson suggests that the whole point of perception is action. For example, when some single-cell organism touches an obstacle, it moves away.

That is the whole point of perception: to move in the right direction, to find food, to not be food—to survive.

Perception serves future action, not insight.

Accordingly, our brain is fully embedded in the material world and responds to the movements around it.

Bergson refers to such a purely physical reaction as pure perception.

Yet he acknowledges that we are more complicated than single-celled organisms. The movements of our environment have to make their way through our complex sensory system with all its twists and turns.

And this leaves us more options on how to act.

So we don’t just react like a single-celled organism, we can choose from a range of potential movements.

But how?

We remember.

2. Memory is temporal

Bergson distinguishes two kinds of memories: Some memories have become part of our body, they are a product of habit. When we go for our usual walk, our body automatically remembers where to go.

But then there are memories that are not habitual, but pictures of the past. For example we can vividly remember that encounter with a cute cat last week.

Even though we have experienced such a situation only once, we can still recall it. It is instantly present.

The habitual memories are part of our body, the other ones are… well…

Warning: Now here comes a philosophical idea that might seem strange to us, maybe even absurd. But hang in here! It is challenging ideas like these that make philosophy fun.

Bergson claims that these memories do not exist in the brain. Our brain merely retrieves them from the past.

What?

If the memories are not in the brain, then where are they?

In our past, Bergson would say.

We are used to regard only physical things as real—like the neurons of our brain. As a consequence, we are tempted to think that things in the past don’t exist anymore. But Bergson disagreed. An object does not cease to exist just because it is somewhere else in space. The chair in the room next door is still there, even though you can’t see it right now.

Similarly a thing does not cease to exist just because it is somewhere else in time.

For Bergson, time is an aspect of reality. Let me put it this way: Is a flower only the physical thing that you see right now, or is it not also a structure in time?

Likewise, maybe you are not just the atoms of your physical body but also your previous movements—and memories—in time. And this personal lifetime or duration is just as real as the atoms of your body.

For Bergson, it is of vital importance that we have access to this personal lifetime.

3. The past is in the present

Because in order to recognise something that we see, we must recall memories that are similar to that thing. We enrich our present experience with our personal memories from the past.

Without any memory we couldn’t recognise anything, we would be limited to the current moment.

Think of how you perceive a melody. You don’t just recognise one tone at a time. Instead, you need to remember the previous tones and anticipate the ones to come.

The same principle applies when we read a sentence or listen to a story.

Perception takes time.

We can move back in time to recall useful memories to make our perception more precise.

According to Bergson, this is what we do when we pay attention.

We actively expand the spectrum of memories to better understand a given situation. Bergson compares this process to the adjustment of a camera lens. Recalling the right memories sharpens our perception of the present.

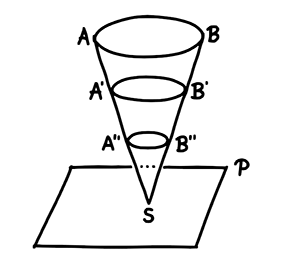

Here is his famous diagram to illustrate that point.

The plane P stands for the present situation, the point S marks our present situation, and the circles AB, A’B’, A”B” represent different memories. The higher up those are in the memory cone, the further back they are in the past.

Now, as much as I can appreciate the sobriety of mathematical language, I will take the liberty to interpret his diagram like this:

We can shift our attention between our immediate material situation and our remotest memories. This movement is akin to a process of abstraction from our body to our ideas.

At the extreme upper end would be the dreamer who is caught up in memories and totally detached from physical reality (academics come to mind). On the lower end would be an extreme pragmatist who is reduced to rash intuitive reactions to the physical environment.

Usually we move somewhere in between those extremes.

Our body evokes memories to recognise the present for our future actions.

Consciousness at the intersection of matter and memory

And it is this combination of your personal body and your personal time that creates your unique experience: your consciousness. Consciousness connects the current physical structure of our body with the temporal structure of our life.

And the temporal aspect is where our freedom lies, because our lifetime, unlike space, is not determined. Matter is predictable, time is not.

So neither are we.

This is why it is so important for Bergson that our memories are not just material traces in our brains. That would make us deterministic machines.

The unpredictability of our lifetime is the foundation of our freedom.

The title of his book “Matter and Memory” emphasises his understanding of our consciousness as the interplay of body and time.

We can cultivate our perception

So while we might not be able to fully live in the present moment, we are free to massively improve how we experience this moment—and ourselves. First of all we can cultivate the conscious shift of our attention. Sometimes we might want to be closer to our body, for instance when we practise Yoga or meditation. At other times we might want to tap into the rich archive of our memories to understand the big picture.

But more importantly we can grow this archive of memories and become connoisseurs. A wine enthusiast can appreciate a fine grape because his memory of previous wines allows him to assess the drink in his hands.

If we have never paid attention to pottery, then even the most splendid Song Dynasty bowl looks just like any other clay pot. But if we have seen plenty of ceramics, or even made some ourselves, we can fully appreciate such exquisite creation.

The more we know, the more we see. This is one of the reasons why I love drawing: When we draw something, we shift our attention in order to see what is actually there. To a certain extent we draw what we remember just as much as we draw what we see. You have to know how to draw a tree if you want to draw that tree. But of course at the same time we see something new and absorb new memories.

If you want to dig deeper

Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory

Henri Bergson, Matière Et Mémoire (french original)

This piece came in exactly at the moment when I am pondering on the topic of "freedom". Thank you so much for distilling the concepts into imageries that now become part of my archive of memories to draw from, when I face a new reality.

I don't remember subscribing to your substack, and yet here I am. Took an action in the past to cultivate my perception in the future? I upgraded to paid.