If you are interested in truth, be it in the form of scientific knowledge or artistic beauty, there is no way around Immanuel Kant’s ‘Critique of Pure Reason’. In this book Kant asked the simple question: “What can we know?”

And his answer is foundational to how we experience and understand the world today.

1. Should we think or should we look?

Before we delve into Immanuel Kant’s solution, let’s have a quick look at two opposing philosophical views of his time.

Rationalism: It is all in our head

One position – which is often attributed to rationalists like René Descartes– considers our rational thinking as the source of all knowledge. Our senses might betray us, but our rational mind is reliable. Perhaps because it was created by a higher power.

Empiricism: It is all out there

An opposing view – usually associated with empiricists like David Hume – suggests that our minds are somewhat empty. Everything we know must have entered through our senses first.

We must observe the outside world to learn what is going on.

Our mind shapes the world

So rationalists think that our mind is built to understand the world through rational thinking—from the inside. Empiricists believe that we learn about the world through observation—from the outside.

Both groups assume that our mind somehow adjusts to the world around us.

Immanuel Kant turns this around.

He says it’s not our mind that adjusts to the world; the world adjusts to our mind.

In other words, how we see the world is shaped by how we see and think. We can notknow the world as it truly is because we can only experience it through our own senses and thoughts.

Our mind filters and shapes what we can know about the world.

So we must understand how our mind works. And this is what Kant’s book is about.

2. We look AND think

Kant agrees with the empiricists that we need observations from the outside. He also agrees with the rationalists that the mind must structure these observations.

And this is how sensibility and understanding work together:

Sensibility

Let’s start with our senses! All we get is raw data from the outside world. This data does not mean anything yet.

Thus, the first thing our sensibility does is to structure that data in space and time.

According to Kant, we don’t know whether space and time are properties of the outside world, but they sure are part of our mind. Remember his premise that the perceived world adjusts to our mind? It is our sensibility that uses time and space to filter and structure what we observe.

Kant says that even mathematics is based on these two “pure forms of intuition”, where arithmetic is related to time and geometry to space.

Understanding

The problem with these impressions, even after they are structured in time and space: There are simply too many and they are too chaotic.

So now it is up to the understanding to reduce and organize this raw input. How? We combine many similar impressions into one object.

We can take this even further: When we see many objects with similar properties, we can name them, for example, as ‘cup’.

We have thereby grouped many impressions under one concept.

A concept is a representation that unifies a group of phenomena.

To understand something means to recognize relationships through concepts. We can now formulate judgments like, ‘The cup is on the table.’

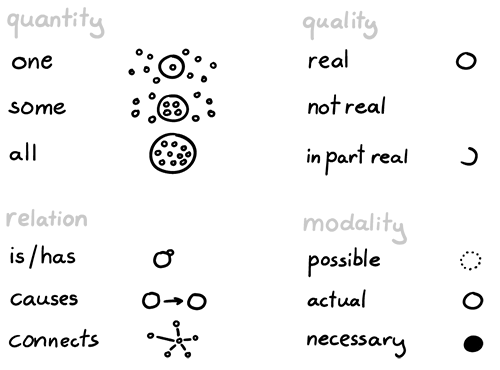

Our understanding determines how we form and connect such concepts. We do this according to certain rules, which Kant calls categories of understanding. These 12 categories include, for example, the recognition of causal relationshipslike, ‘If I drop the cup, then it will break.’

What makes our insights objective, says Kant, is that every act of understanding must follow these categories. The categories and how our mind applies them are the reliable constant that makes objective knowledge possible.

Let’s keep in mind: We do not have direct access to the things in themselves but we dohave access to the intuitions, which they invoke in our sensibility. We combine these intuitions of the world with our concepts of thinking and this is how we arrive at insights of the world!

But the story is not over yet.

3. What we cannot understand

Our understanding tempts us to think beyond what we can perceive. We can think about thinking. Kant calls this reason.

In rather poetic terms he describes our mind as an island, which we can map out clearly. This island is placed in an ocean of unknown “things in themselves” and is fed by waves of data and forms its own insights.

But the core of this island – reason – is not satisfied with this limited existence.

For instance we might want to understand the infinity of space. Or how an infinite space is possible? And if it is not infinite… then what is beyond its borders? When did time start? Is there a cosmic principle that unites everything, such as God?

Kant says we can ponder these metaphysical questions but the tragedy is: we can neveranswer them with certainty. They are mirages out there in the ocean which we can never know. There is no solid ground beyond our little island.

4. What we can know—and how

Finally, we can get to Kant’s answer. When we gain insights about the world we receive input from the outside and then actively structure it using a fixed set of principles, or categories of understanding. We need both: perceptions from the outside and the ability to order and unify them in our mind. Or as he put it:

“Thoughts without content are empty; intuitions without concepts are blind.”

There are things though, that are beyond the understanding of this apparatus, like the infinite cosmos, the soul or God.

One of the cool things about Kant is that he has integrated a huge amount of philosophical thought into a coherent system. So while he was contributing some of the most original ideas he also structured and connected existing ideas by other great thinkers.

And this magnificent system—whether we agree with it or not—has become a monumental bedrock for inquiries into the nature of knowledge in Science, Art and of course the current endeavors of Artificial Intelligence.

In another book, ‘The Critique of Judgment,’ Kant connected our search for understanding with how we find beauty in the world. But let’s save his views on beauty for another day.

One more thing

I have oversimplified Kant’s book here to an almost questionable extent, trying to pack it into a couple of paragraphs with some cute illustrations. The “Critique of Pure Reason” is a fantastically complex and rich book. You can spend a lifetime exploring this monument, and in fact many people have.

My intent here is not to provide you with a complete understanding of this book – I couldn’t, even if I tried. The best I can hope for is to wet your appetite to embark on the adventure of reading it yourself!

Sparks some thoughts, thank you for the great summary with very good illustrations!